NOW! That’s what I call Planning Reform Volume 267

The title page of NPPF reform; too jazzy?

It wouldn’t be the UK if we didn’t have a Government consultation landing immediately before Christmas – and it arrived, courtesy of the snazzily titled Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. This was a rather important one – the Government’s consultation document on proposed reforms to national planning policy and an indicative mark-up of its National Planning Policy Framework.

Both were extensively trailed before publication and appear to be a return to two classic recent Governmental themes: an attempt to quell backbench revolts, particularly in the South East, on what gets built where; and ‘Goveism’, a reflection of the returning Secretary of State’s own views of what constitutes quality development.

But what does it amount to? This report offers our initial ‘non planner’ view on the proposed changes ahead of us formally submitting our views to Government well ahead of their consultation deadline of the 3rd of March: that changes to the NPPF amount to a ‘watering down’ of planning and will further put the brakes on housebuilding and growth in the UK. Huge thanks to those wise owls who’ve been here before including Simon Ricketts, Zack Simons, Catriona Riddell, Sam Stafford and others in helping inform this rather depressing conclusion…..

At least the changes are ‘clear’

First of all, we have enormous sympathy for the Civil Servants that have once again picked up tools, under yet another Secretary of State, to alter policy to meet the pressing political needs of the day. Whilst we were awaiting a promised ‘new NPPF prospectus’ in the autumn, this was waylaid by a backbench rebellion on planning amendments to the Levelling Up Bill ostensibly informed by it.

Beating a hasty retreat, civil servants have ‘marked up’ changes to the existing NPPF. Presentationally, this makes a lot of sense – as Simon Ricketts pointed out in his recent blog:

“I am relieved that for once what we have been presented with is comprehensive and well explained. This is no longer a “prospectus” as to what the nature of the proposed changes but includes the actual proposed wording of the revised NPPF itself.”

This enthusiasm is replaced however by a general sense of gloom when the contents are considered. This begins with the proposed changes to the NPPF’s first paragraph…..

House of Commons research papers show the issue at hand

Don’t mention the numbers: I mentioned it once

Let’s get straight down to first principles. Should the UK build 300,000 homes per year, its apparent target? We’d argue that the proposed new first paragraph of the NPPF waters down the UK’s commitment to provide enough new housing:

It provides a framework within which locally-prepared plans can provide for sufficient housing and other development in a sustainable manner.

The stated intention of the 2012 NPPF was to ‘significantly boost the supply of housing; by emphasising ‘sufficient housing’, this leaves the level of housing supply open to interpretation, conjecture and (frankly) battle. As Sam Stafford points out within his excellent 50 Shades of Planning blog, this theme continues through the rest of the changes:

“From softening land supply and delivery test provisions, taking in additional policy protection to agricultural land, and then to explicitly indicating the types of local characteristics that will justify a deviation from the standard method, the unstated intention that runs through the consultation document is to reduce the supply of housing.”

What about ‘the standard method’ I hear you ask? The document now refers to the Standard Method only being considered as a ‘starting point’ (Paragraph 61) for the number of homes an area should deliver. Given the debate about the 300,000 homes, the revised NPPF could have made a commitment to its revision or, as Sam points out, “reverting swiftly back to local objective assessments of need.” What we have instead is wriggle room for local authorities to plan for less than whatever an apparent target is. We fail to see how this acts as an incentive for local authorities to deliver the up-to-date local plans that local people and businesses need for surety.

Housing crisis? What crisis?

The apparent rise of sustainability – but what about Transport?

E-scootering: one of a number of new transport initiatives not referred to

In better news, the proposed revisions appear to emphasise sustainability to a far greater degree than before, reflecting both increased policy alignment to the UK’s net-zero goals and the rise of biodiversity net gain and nature recovery in bringing forward development.

Sadly, this is also subject to significant conjecture. In the same way that ‘sufficient housing’ doesn’t fill us with confidence, neither does the catch-all line ‘in a sustainable manner’. Paragraph 7 has the following proposed change (italicised):

“The purpose of the planning system is to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development, including the provision of homes and other forms of development, including supporting infrastructure in a sustainable manner.“

To emphasise this lack of clarity, the proposed NPPF follows on by doing two sustainability-linked elements well and completely ignoring another. It does the right thing by retaining the perfectly valid Paragraph 11(a) on the basis of plan-making:

For plan-making this means that:

a) all plans should promote a sustainable pattern of development that seeks to: meet the development needs of their area; align growth and infrastructure; improve the environment; mitigate climate change (including by making effective use of land in urban areas) and adapt to its effects

New paragraphs 160 and 161 also better support the required decarbonisation of the UK by proposing that when local authorities are determining planning applications for renewable and low carbon development, they should:

approve an application for the repowering and life-extension of existing renewables sites, where its impacts are or can be made acceptable. The impacts of repowered and life-extended sites should be considered for the purposes of this policy from the baseline existing on the site

…and:

To support energy efficiency improvements, significant weight should be given to the need to support energy efficiency improvements through the adaptation of existing buildings, particularly large non-domestic buildings, to improve their energy performance (including through installation of heat pumps and solar panels where these do not already benefit from permitted development rights). Proposals affecting conservation areas and listed buildings should also take into account the policies set out in chapter 16 of this Framework.

So far so good – and we support these revisions. The balloon is well and truly punctured however when we move to Section 9 on ‘Promoting Sustainable Transport’. Absolutely no revisions are suggested, despite some fairly major technological advances and some excellent work from the real estate industry showing the benefits of moving away from the ICE-powered car. A missed opportunity? We certainly think so.

Whither ‘beauty’?

Next, we come onto another imponderables – what defines ‘beauty’ in development? Ask ten different real estate professionals and you’ll get ten different answers – yet Michael Gove, a regular exponent of the issue, has insisted on it making its way into the proposed revisions.

Paragraph 20 suggests the following change:

Strategic policies should set out an overall strategy for the pattern, scale and design quality of places, (to ensure outcomes support beauty and placemaking), and make sufficient provision.

Type in ‘NPPF beauty’ into Google and the most recent Government reference sets out a landmark design event in 2021. What beauty means for places or housebuilding is not specified within the guidance, leaving it again for local authorities to determine what they think is best (within limited resources) and to risk the consequences – bar a bizarre paragraph on mansard rooves (see below).

This lack of specificity, ostensibly to satisfy close interest groups, doesn’t do anyone any favours.

(Don’t) Love Thy Neighbour

Goodbye then ‘the duty to co-operate’, the duty for local authorities to work together to accommodate each others development where required. Paragraph 35 deletes the following line in local authorities being required to ‘positively prepare’ their plans:

….and is informed by agreements with other authorities, so that unmet need from neighbouring areas is accommodated where it is practical to do so and is consistent with achieving sustainable development;

It’s well-recognised that voluntary collaboration, on the whole, hasn’t worked in England – and as Catriona Riddell wisely points out, we have twelve years of evidence to prove it. This lack of ‘strategic planning’ is a clear inhibitor to good growth and productivity – so why doesn’t the NPPF beef up strategic planning arrangements, rather than withering on the vine?

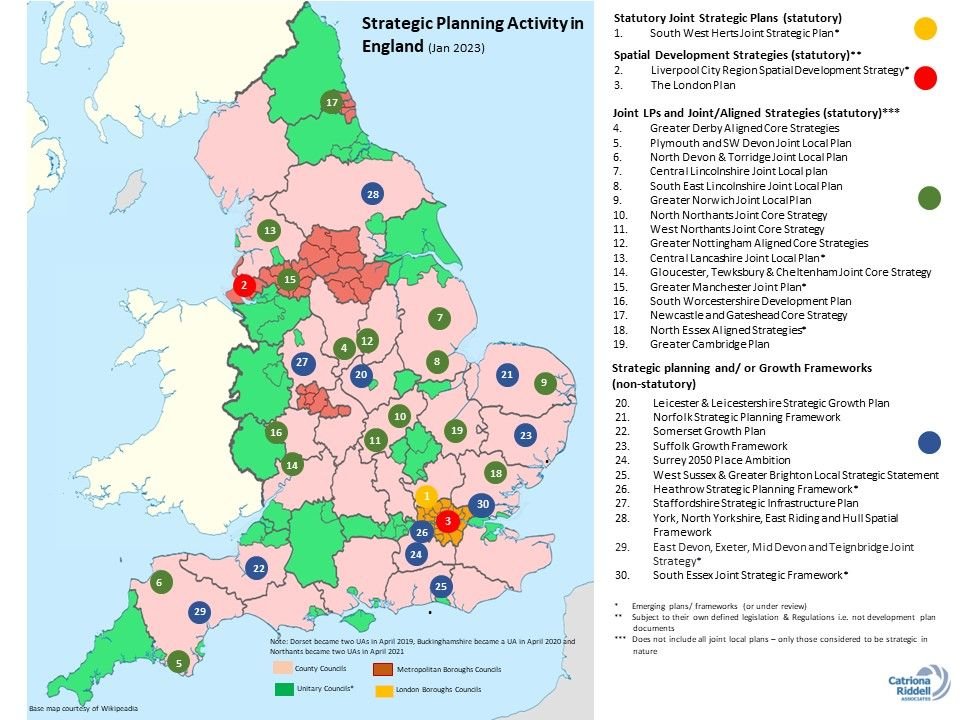

The decline of strategic planning in map form

Catriona’s graphic above shows how little strategic planning now takes place and we’ll be joining her call for the NPPF to have proper due regard to it. Read more of her sage views here.

Expect more green belt revolts in 2023

A push for a new Urbanism? (But don’t mention the Green Belt)

An apparent push of the proposed NPPF is for 20 of the largest towns and cities being expected to do much of the heavy lifting in increasing the UK’s housing supply, with a 35% uplift applied on top of the existing ‘standard method’.

The new Paragraph 61 explains this change in more detail:

The Standard Method incorporates an uplift for those urban local authorities in the top 20 most populated cities and urban centres. This uplift should be accommodated within those cities and urban centres themselves unless it would conflict with the policies in this Framework and legal obligations

In doing so, brownfield and other under-utilised urban sites should be prioritised, and on these sites density should be optimised to promote the most efficient use of land, something which can be informed by masterplans and design codes. This is to ensure that homes are built in the right places, to make the most of existing infrastructure, and to allow people to live near the services they rely on, making travel patterns more sustainable.

Is this actually achievable in practice though? Learned colleagues have pointed out two key elements which may prevent it being delivered:

– Greg Dickson of Stantec has completed research that shows that 18 of the 20 were already meeting the requirements of the housing delivery test, but only delivered 28,000 homes of the c. 200,000 homes built nationally. If we are to deliver 300,000 homes per year across the UK, we’ll need to go much further than asking a small number of authorities delivering their numbers to step up.

– Catriona Riddell also emphasises that they will be expected to deliver this within their own boundaries unless their neighbours agree to help. There is one major issue with this:

But as nearly all of the towns and cities identified are surrounded by Green Belt and other constraints, what are the realistic chances of this happening without any effective approach to strategic planning? There is therefore likely to be a very big unmet need floating around these city-regions!

With the duty to co-operate disappearing and no emphasis being placed on strategic planning, how does the Government expect local authorities to work together properly in this febrile environment to tackle the Green Belt? We’ve said before that without proper Green Belt reform the UK will not deliver the number of new homes it needs to; simply asking 20 cities to deliver new targets without supporting them or others with the tools to do so simply does not cut it.

We like mansards, but do they need to be in the NPPF?

Have whatever roof you like, providing it’s Mansard

Hands-up from our founder: we did not have ‘Mansard Rooves’ on our planning phrase bingo card and it is quite incredible that at this time of stagnant growth and continued development under-delivery that this design feature gets its own paragraph within the revised NPPF.

Within Paragraph 122, the revised NPPF asks local authorities to:

allow mansard roof extensions where their external appearance harmonises with the original building, including extensions to terraces where one or more of the terraced houses already has a mansard. Where there was a tradition of mansard construction locally at the time of the building’s construction, the extension should emulate it with respect to external appearance. A condition of simultaneous development should not be imposed on an application for multiple mansard extensions unless there is an exceptional justification.

We only have three questions in relation this: why, why and why? Its inclusion is utterly utterly baffling when you consider what this document should be about and frankly what’s at stake – the sustainable and inclusive growth of the UK as a nation.

A depressing conclusion: who will plan for growth in this febrile political environment?

We wish we were more upbeat dear readers, but we need to be honest about what we think these proposed changes signify: Positivity to passivity – a movement from a ‘plan-led’ system focused on growth to a ‘just do enough’ system focused on politics.

Local plan delivery already started to drag ahead of the proposals being published, with Planning Resource reporting on 19 December 2022 that:

– Horsham District Council delayed its cabinet meeting to consider its proposed Regulation 19 consultation draft plan from 15 December 2022;

– Mole Valley District Council has paused preparation of its new local plan; and

– The Vale of White Horse and South Oxfordshire District Councils have announced an 11 month delay to the preparation of their emerging joint local plan.

This delay will only increase during the consultation phase – and by the end of it, if the NPPF remains in its consultation form, local authorities will end up preparing plans with lower housing and commercial development numbers anyway. We’ll be reflecting our trenchant views by the consultation deadline of the 2nd of March, both as a company and with other groups; get in touch if you want to register joint or combined submissions and we’d be delighted to work with you.